I’ve been struggling through the first eighty-four pages of Elizabeth Bishop The Complete Poems 1927-1979 and finding it impossible to identify with most of the poems as they are long, detailed examinations of ordinary, everyday situations which seem to lead nowhere. While it is remarkable that someone actually pays such close attention to everyday settings, most of the poems just plain bore the INTP in me.

Other more symbolic poems like “The Weed” are more interesting, but nearly impossible to comprehend, as if the narrator’s dream were recorded directly on to the page without any effort to interpret it.

Perhaps it is finding “The Fish” in this context that made it seem so extraordinary, a poem of minute detail that explodes into a vision of nature:

The Fish

I caught a tremendous fish

and held him beside the boat

half out of water, with my hook

fast in a corner of its mouth.

He didn’t fight.

He hadn’t fought at all.

He hung a grunting weight,

battered and venerable

and homely. Here and there

his brown skin hung in strips

like ancient wallpaper,

and its pattern of darker brown

was like wallpaper:

shapes like full-blown roses

stained and lost through age.

He was speckled with barnacles,

fine rosettes of lime,

and infested

with tiny white sea-lice,

and underneath two or three

rags of green weed hung down.

While his gills were breathing in

the terrible oxygen

— the frightening gills,

fresh and crisp with blood,

that can cut so badly —

I thought of the coarse white flesh

packed in like feathers,

the big bones and the little bones,

the dramatic reds and blacks

of his shiny entrails,

and the pink swim-bladder

like a big peony.

I looked into his eyes

which were far larger than mine

but shallower, and yellowed,

the irises backed and packed

with tarnished tinfoil

seen through the lenses

of old scratched isinglass.

They shifted a little, but not

to return my stare.

— It was more like the tipping

of an object toward the light.

I admired his sullen face,

the mechanism of his jaw,

and then I saw

that from his lower lip

— if you could call it a lip —

grim, wet, and weaponlike,

hung five old pieces of fish-line,

or four and a wire leader

with the swivel still attached,

with all their five big hooks

grown firmly in his mouth.

A green line, frayed at the end

where he broke it, two heavier lines,

and a fine black thread

still crimped from the strain and snap

when it broke and he got away.

Like medals with their ribbons

frayed and wavering,

a five-haired beard of wisdom

trailing from his aching jaw.

I stared and stared

and victory filled up

the little rented boat,

from the pool of bilge

where oil had spread a rainbow

around the rusted engine

to the bailer rusted orange,

the sun-cracked thwarts,

the oarlocks on their strings,

the gunnels — until everything

was rainbow, rainbow, rainbow!

And I let the fish go.

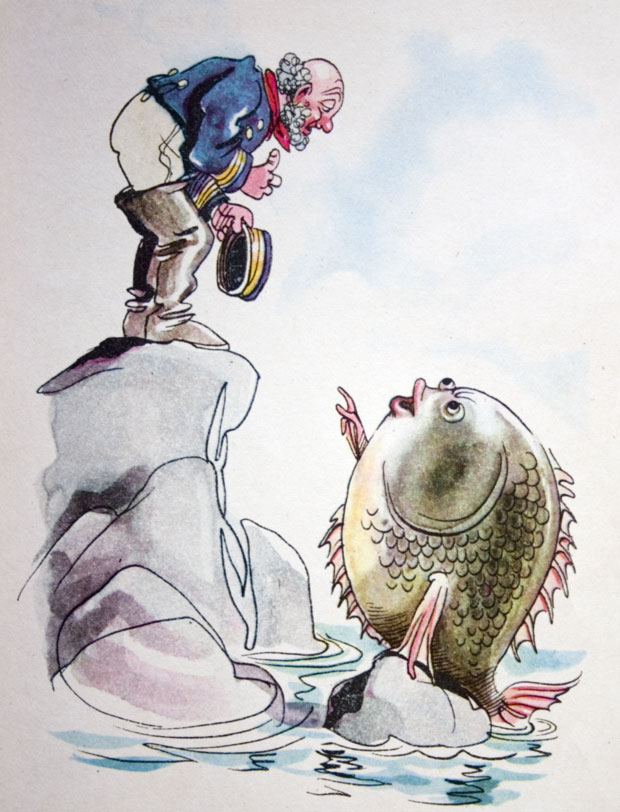

Perhaps I merely liked this poem because it brought back old memories of the picture of the magical flounder in Grimm’s fairy tale “The Fisherman’s Wife.�?

Though Bishop goes out of her way to paint a “realistic picture�? of her fish, in the end it’s the “fabulous�? aspect of the fish that nets this reader.

The poem also reminds me of Faulkner’s fable of “The Bear,�? where an ancient, larger-than-life bear represents Nature. In terms of fish tales, this is The One That Got Away, the giant fish fishermen the world around talk about when they gather. And the only way one can hang on to This Fish is to let it go, to continue the legend.

Of course, it could be that I liked this poem simply because it reminds me of the joy I sometimes experience when I’m totally immersed in the moment in a particular place, a brief moment when I feel at one with nature and myself.

Not surprisingly, this much-anthologized poem has inspired considerable commentary, some of which is discussed here.