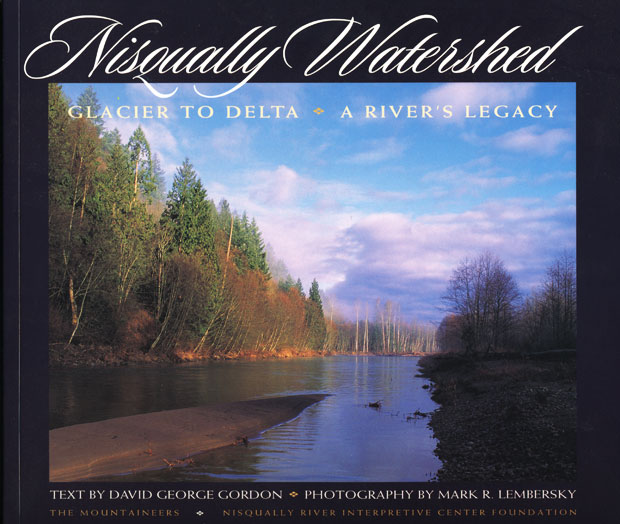

From the moment I picked up Nisqually Watershed: Glacier to Delta — A River’s Legacy, I knew I had to own it. The photographs were too beautiful to put down, as revealed by the cover photo. I wasn’t disappointed with the many photos that make up a large part of this book. Seeing them nearly recreates the river’s presence.

I was also delighted by several smaller illustrations that accompanied the text, like this picture of a cliff swallow.

These illustrations not only added variety to the book, but served as a visual balance to larger photographs on opposing pages. Though it’s more than a coffe table book, it can certainly compete with most of those kinds of books that I have in my front room. It’s a visual delight.

Unfortunately, I wasn’t quite as delighted by the copy that accompanies the pictures. Perhaps it was merely a matter of not meeting the expectations set by the graphics, but despite some inspiring passages, the prose seldom reaches the level of this passage:

Origins of the Upper Watershed

For the first droplets of the Nisqually River water, there is nowhere to go but downhill. The thin topsoil cannot absorb the tiny pearls of moisture, and the sparse plants lack amply developed root systems to draw them in. Thimble sized drops coalesce, trickling in rivulets down the slopes of Mount Rainier. Rivulets merge, forming small streams.

Each new stream carries tiny particles of rock, the pulverized aftermath of the glaciers’ ebb and flow. No bigger than plaster dust, these particles are called “flour” a fitting name for any material produced by the mountain’s grindstone and the weight of the Nisqually Glacier’s slow moving mill wheel.

Tinged the color of chocolate milk, the flour laden water sweeps over a field of cobbled rocks deposited in previous eons at the glacier’s foot. The young river barely keeps to its cobbled bed in this steep upper stretch. It jostles and tugs at each rock in its path, coursing ahead with the youthful exuberance of a new river.

The energetic stream finds other new snowmelt sources, some milky and some unusually clear due to nonglacial origins. As it tumbles downhill, the stream divides into two parallel streams for a stretch, then soon reunites in a pattern known as “braiding” for its strong resemblance to plaited hair.

Despite some disappointment with the rather generic copy, I do have a better historical view of the river than I had before and better understand the forces that threaten it. I suspect those less familiar with the history of this region might find the copy more more interesting than I did.

Hopefully the book will inspire those who love the Nisqually watershed to continue to provide the protection a health river demands which was obviously the intention of The Mountaineers and the Nisqually River Interpretative Center Foundation, publishers of the book. I will say this book came as close as anything I’ve found so far to feeling like “home” to me. It may be just about the Nisqually, but it feels like many of the rivers flowing from the Cascades to the Puget Sound. Unfortunately, while making your realize how valuable the Nisqually is it also makes you realize how much has been lost in most of the areas north of here.