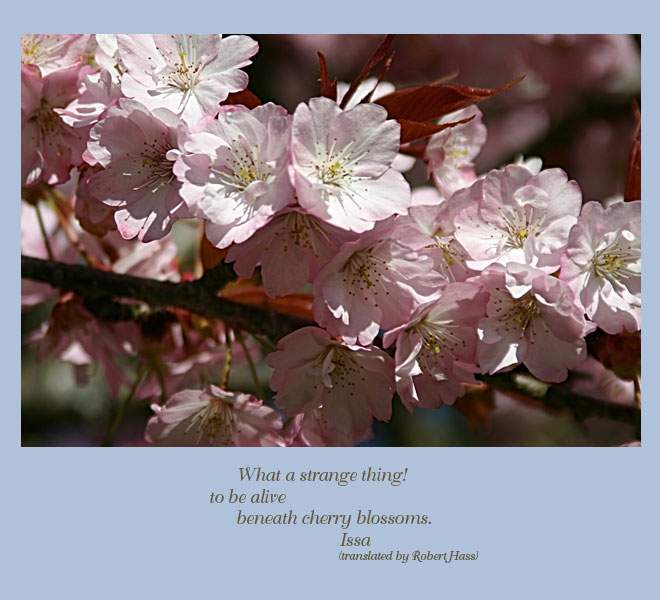

My recent attempts to put words to photographs I’d taken once again led me back to haiku, and, in particular, to Robert Hass’ The Essential Haiku: Versions of Basho, Buson, and Issa, another of many books I’d been intending to read.

Needless to say, it doesn’t take any more of a reason than that to settle down with a book as good as this one. So far, I’ve finished a third of the book, the section on Basho. I’ve particulalry enjoyed the historical introduction to the poets. Even more so, I’ve been fascinated by the inclusion of parts of journals that incorporate haiku poems.

One of my favorite poems, with introduction, is:

Unchiky, a monk living in Kyoto, had painted what appeared to be a self portrait. It was a picture of a monk with his face turned away. Unchiku showed me the portrait and asked for a verse to go with it. Thereupon I wrote as follows–

You are over sixty and I’m nearing fifty. We are both in a world of dreams, and this portrait depicts a man in a dream. Here I add the words of another such man talking in his sleep.

![]() You could turn this way,

You could turn this way,

I’m also lonely,

![]() this autumn evening.

this autumn evening.

Obviously it’s difficult to pick a favorite from a selection of classics like this, but this one:

![]() A caterpillar,

A caterpillar,

this deep in fall —

![]() still not a butterfly.

still not a butterfly.

seems particularly poignant to me at my age.

And somehow this one:

![]() They don’t live long,

They don’t live long,

but you’d never know it —

![]() the cicada’s cry.

the cicada’s cry.

reminds me of several of Emily Dickinson’s poems.