As I’ve considered and reconsidered “Conquistador,” I’ve realized that one of my problems with the poem is that I, like Dorothea, am unconvinced that Cortes’ conquest of the Aztecs was a “noble” victory as depicted in Diáz’s account and, consequently, in MacLeish’s poem. I generally tend to identify with the native people, particularly when, as in Cortes’ case, the victors seem to have been driven more by a desire for gold than by any noble cause. While reviewing the background of Cortes’ victory I found another very different perspective of the war at “The Aztec Account of the Spanish Conquest of Mexico”, an account that one would surely need to consider to gain a true understanding of the Conquistadors. Luckily, resolving this complex question isn’t vital in order to understanding MacLeish’s poem and his philosophy.

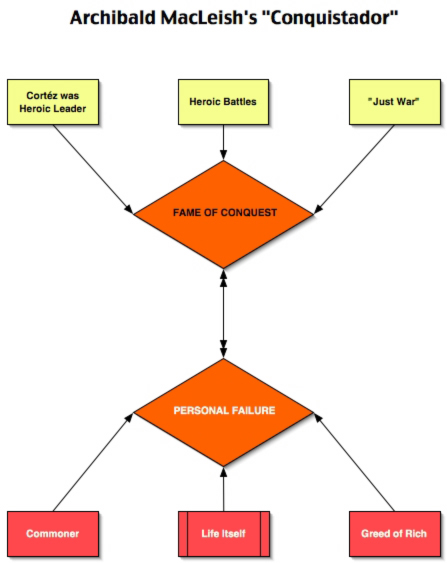

That said, in order for the poem to work MacLeish needs to establish how glorious the victory was and that Bernal Diaz’s was an important member of that victory. An important step in doing so was to show Cortes’ genius in battle. Next he needed to show, just as Diaz had attempted to do, that it was a “just war.” Otherwise, one could easily argue that Diaz’s final misery was God’s just reward for his evil acts. Finally, easiest of all, MacLeish needed to show how truly magnificent this victory was, as a small force of Spaniards defeated hordes of evil enemies in scenes reminiscent of Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings.

Cortes isn’t the central character in the poem, but he is shown repeatedly as a heroic leader. First, he is shown to be determined leader:

"Did we come to the gate of a ground like this to return from it?

"If he had no writ of Velasquez’s hand let him find one!

"Let him establish a king’s town for the birds

"Taking his writ from the Emperor Charles and the spiders

"And damned to Velasquez’s deed!"

Although he had no orders allowing him to invade Mexico and he was order to withdraw by the governor of Cuba, Cortes never wavered in his determination to explore and conquer Mexico.

Cortes used guile and military genius to defeat a superior enemy. When the emissaries from Montezuma came in an attempt to win Cortes to their side, or at least to prevent his further advance, Cortes pretended to thank the emperor and expressed a desire to meet him personally:

"Now does he send you from his endless thousands

"These and this treasure: in Tenochtitlán

"Armies- are harvested like summer’s flowers":

So did he speak and he pointed with raised hand

Westward out of the sun: and Cortés was silent

And he looked long at his feet at the furrowed sand:

And his voice when he spoke was a grave voice without guile in it-

"Say that we thank him well: say also

"We would behold this Emperor": and he smiled:

Later, in the final victory after having been initially driven out by superior numbers, Cortes planned a siege that defeated the Aztecs:

And we marched against them there in the next spring:

And we did the thing that time by the books and the science:

And we burned the back towns and we cut the mulberries:

And their dykes were down and the pipes of their fountains dry:

And we laid them a Christian siege with the sun and the vultures:

And they kept us ninety and three days till they died of it:

And the whole action well conceived and conducted:

Finally, Cortes was an inspirational leader who wouldn’t allow his troops to give into defeat when they seemed hopelessly outnumbered:

And Cortes was wild with the night’s work –

"Had we brought the

"’Whore of death to our beds and our house to serve us?

"How should we profit by these deeds? And we thought our

"Ills were done! And the wheel of our luck turned!

"And the toss was tamed to our hands!

and

All that day and into dark we fought:

And we lay in the straw in the rank blood and Cortés was

Hoarse with the shouting – "… for a man was wronged and a

"Fool to suffer the Sure Aid but to best it and

"Fight as he might: and he prayed all of us pardon

"And grace if he spoke our hurt: but we were men:

Heroic or not, it’s hard to deny that Cortes was a remarkable leader.

Of course it matters little how heroic your leaders are if you are fighting an unjust war. Such leaders may become infamous, but they can never truly be heroic. The poem does not provide a formal argument over the justification of the war, but MacLeish uses several passages from Diáz, to support the idea that it was a just war, if not a holy one. One of the earliest passages in the poems cites the Spaniards’ reaction to the priests’ sacrifices:

New-spilled blood in the air: many among us

Seeing the priests with their small and arrogant faces:

Seeing the dead boys’ breasts and the idols hung with

Dried shells of the hearts like the husks of cicadas

And their human eyeballs and their painted tongues

Cried out to the Holy Mother of God for it:

Diáz notes that in their earliest meetings that Indians who were oppressed by the Aztecs hated them:

"Montezúma the king’s land! Of our people

"Clear to the sea’s edge was the river corn:

"And they came from the west with their hard eyes and their eagles:

"Once we were short of spears: once were the fords deep:

"Now they take what they will in the whole land:

"They rut in our daughters’ beds: it is evil fortune:

"We have no name of a man now: our ancestors –

"They that planted the orchards: they were Totónacs:

"I that speak this was a free-born man:

"Beware of the land Colúa you that go to it!"

Several epithets identify the Aztecs as a force of evil (perhaps Bush could increase his appeal to intellectuals simply by borrowing epithets from MacLeish’s poem):

“The falsifiers of things seen!/ The defamers of/ Sunlight under the name of our sky!/ and we slew them” and one that seems uniquely MacLeishean, “And they would have destroyed us in that place: the debasers of/ Leaves! of the shape of wild geese on the waters!”

The Tenth Book which begins with the description of a virtual Paradise, and ends with a sacrifice of a young boy by the Aztec priests, the apparent price of maintaining this heathen paradise offers the most convincing argument that the Spaniards saw the Aztec priests as ministers of the Devil. The book begins:

O halcyon! 0 sea-conceiving bird!

The bright surf breaking on thy silver beaches

continues:

We were like those that in their lands they say

The steers of the sun went up through the wave-lit orchards

Shaking the water drops and those gold naked

Girls before them at their dripping horns!

Despite their feeling that this is paradise, the Spaniards were unwilling to pay the price for continuing to live here:

And they passed with their cries at dawn and their deep

drums:

And we saw them go by the stone courts and the cages:

And all clean and with coarse lime and the temple

Steep in the reach of the sky

and the boy was slain!

No matter how hypocritical or greedy the Conquistadors may have been, it is difficult to justify the sacrifices that the Aztecs demanded of the other tribes they had conquered.

Finally, the battle scenes depicted in the poem would be a movie director’s delight. It was a real High Noon where, for those still capable of such illusions, the “good guys defeated the bad guys:”

And they came like dogs with their arms down: and their

faces

Painted and black and with death’s eyes and their breasts

Quilted with cotton and their naked arms:

And the hard hammer of sun on the gold: and their crests like a

Squall of rain across the whitening barley –

We that were mortal and feared death – and the roll of the

Drums like the thud in the ear of a man’s heart and the

Arrows raking us: rattle of metal: the goad

Stuck in the fat of the hand: and we standing there

Taking the sting of it. .

No! we were good soldiers –

And in a later battle:

They fell by scores and they came again by their hundreds:

And the blood of our veins was run in the earth with our victories:

Day after day we fought and we always won!

And we sent them word they were well wealed: and to think of it:

And they came again with their crow’s cry and their feathers:

And they fought us back in the brake: and our bellies sickened:

And we saw soon how our bodies were near death

And how we should take that battle with our lives

And pass them by with our bare bones into Mexico –

No matter what we might personally believe, Diaz seemed convinced that with the Grace of God that the Conquistador’s were able to defeat the forces of evil:

And the plumes sawed in the sun like maize: and we feared them and

Fought blind and with God’s grace we came out of it:

And we lay beyond the mountains for that year.

In many ways Cortes’ victory seems like the kind of victory that only happens in fantasies. Little wonder that he and his men may have felt that they were blessed by God.