If Mono Lake birding was a disappointment, Bodie, a nearby ghost town, was an unexpected pleasure. In fact, I’d never heard of Bodie until the day before when a birder at the Mono County Park told me that he never went by without stopping at Bodie. I really didn’t expect much since I’m generally not into “historic” sites, but we spent more than half a day visiting the site, and I’ve spent longer than that playing with the photos and still haven’t finished with half of the shots.

Here’s an untouched shot that shows two of the older buildings in the town. I suspect that the rock house was one of the oldest homes, particularly since there was nary a tree in sight around the town.

There’s nothing wrong with the shot; it’s certainly a better shot than most of the visitors would get with their phone cameras. It may be “realistic,” but it doesn’t really capture the “feelings” generated by this mining town which was founded in 1859. 200, 000 annual visitors don’t come to visit ruins, they come to recapture the feeling of California’s great gold rush.

The following photos attempt to convey the sense of history that I got from the town, providing a window into the past. This was my first attempt to capture that feeling.

In this picture the house is actually quite close to the way it looks today, colors and all. I’ve just turned the background to black and white and given the shot a sepia tone.

This shot is a little more radical. Everything in the photo, including the house, has been “antiqued,”

as I attempted to convert the photo into an “aged” photo, one taken close to the time the houses were actually built.

This photo was taken through a very dirty window with a lot of morning glare.

The original photo is clearer than this, but I preferred to “rough” things up a little. I thought that I’d lived in some pretty drab shacks in my early life, but even the poorest of them looked like mansions compared to this.

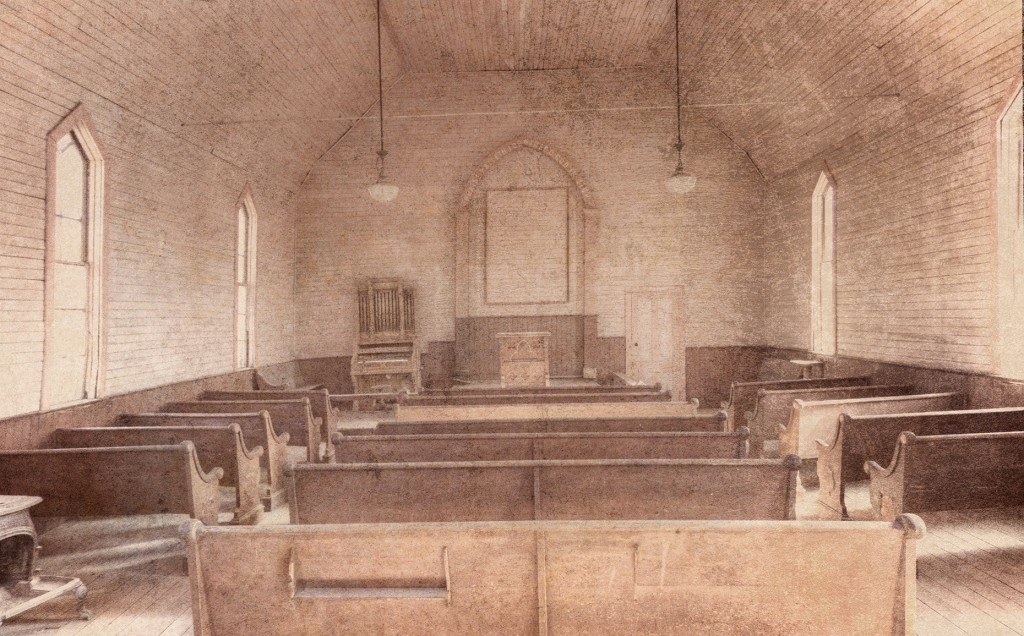

I took a different approach in this shot of the community church whose interior seemed to convey a sense of simplicity and dignity.

This last shot was taken in the museum. I was shocked how much the colors popped when it was rendered in Photomatix Pro 5 since it’s much brighter than it seemed .

I must admit that I was only mildly interested in the personal artifacts found in the museum but was drawn to this painting because it offered such a stark contrast to the desert setting of the town.