I’ve been absorbed in Rollo May’s My Quest for Beauty: … heroes and ecstasy, a personal story of redemption for several days now. I’ve taken so many notes that it’s going to take a while to sort out my ideas, but this passage from late in the book struck me as a perfect example of the kind of peak-experience that Maslow was talking about in his book:

We arrived in Chamonix after dark. Our room in the inn had a large picture window to the southeast, and in the darkness we could see the vast dark lines of Mt. Blanc, silent lord of the entire horizon. On the windowsill of the room was the customary box of geraniums which made a foreground over which we could feel and dimly see the presence of the great mountain.

The next morning I sat on the windowsill for half an hour intensely concentrating on the mountain peak. I cleared my mind of everything and held my gaze stead- ily on the great cone of glowing snow. As I gazed for the first part of the half hour, Mt. Blanc remained a realistic mountain, pure ivory white, incredibly beautiful against the deep blue of the morning sky.

Then, as I continued to concentrate on it, the mountain gradually changed before my eyes into another form. It became abstract. It was now, as the underlying form emerged, composed of disembodied squares and circles and planes. I loved it still, as I love the cubist paintings by Picasso and Braque in the first decade of this century. The mountain form seemed to be painted on a canvas, it was disembodied, pure form with no weight or movement. Or one could as easily say, the mountain form was all weight and all movement; with living form it does not matter, as Brancusi illustrates in his sculptures of a golden line soaring up from its base which he rightly calls “Bird in Flight.”

But as I continued to concentrate steadily on it, this weightless form gradually changed again. The vast mountain took on a body, now organic, three-dimensional. It became a new being on a new level. Now I saw it in a living depth. The glowing ivory forms had come together again into an organism, not personal but

neither was it impersonal. It seemed to be pure form. I felt more than saw an embodied structure, now an ultimate form, part of the universe as I was also. The mountain, like myself looking at it, embodied a uni- verse of beauty and meaning.

Since that day, this experience of my concentration on Mt. Blanc has remained vivid in my mind. Back in New York, later, when I looked out the window of my office on the 25th floor high above the Riverside Drive, I saw in the delicate skyline of New York also pure form-now pure lace. The clouds above the city like- wise assumed the forms I had seen in Chamonix, and as I walked home at night the giant elm trees on Riverside Drive took on this same significant form, all part of the same universe.

This experience of living forms, this embodied being, took me out of myself. Whenever I called it out of the past and into my mind again, it gave me a new experience which was beyond living or dying. The feeling was oceanic, as Freud or Einstein would say; it was my participation in the Being of the universe.

Such an experience cannot be said to exist only in my imagination, nor is it solely a kind of “telepathy” emerging from Mt. Blanc. The experience is both inner and outer, both subjective and objective. It is a fusion of my imagination and the emanating form of the mountain.

This is an illustration of ecstasy. The word comes from the Greek ex-stasis, meaning to stand outside of, or above. It is also self-transcendent. It gives one the experience of going beyond, or absorbing the old self, and a new self, or more accurately an enlarged self, takes its place. To put it in psychoanalytic language, my ego was not denied but absorbed. My self was enlarged by participation in a new being which happened in this case to be the form of Mt. Blanc.

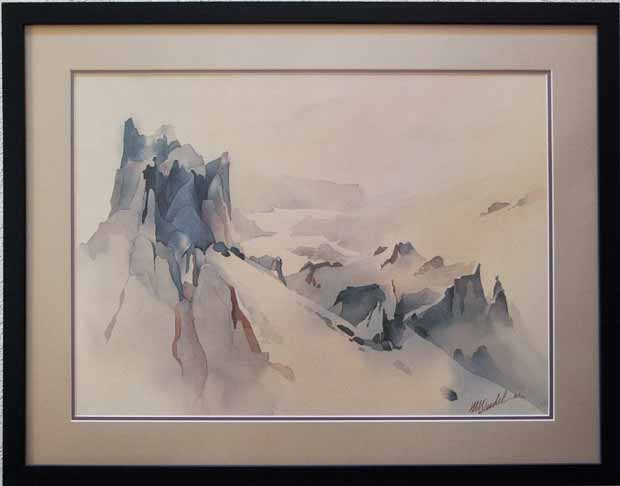

I’ll have to admit this passage probably struck me so strongly because it reminded me of a print I’ve had hanging in my house for 26 years. I bought it right after my divorce from my first wife. I couldn’t afford furniture, even a bed or chest-of-drawers, but I knew I had to have this picture the moment I saw it. I stapled it to the bedroom wall, and it stayed there for ten years until Leslie finally bought a frame for it.

It also struck me that most of my own peak-experiences have taken place while hiking or backpacking in the mountains. Perhaps that’s to be expected from someone who grew up in Mt. Rainier’s shadow and who loves Japanese mountain prints. May’s book made me wonder how much those peak-experiences were influenced by the art I love, both poetry and paintings. I suspect they are so interlinked that it would never be possible to know how important one area is.