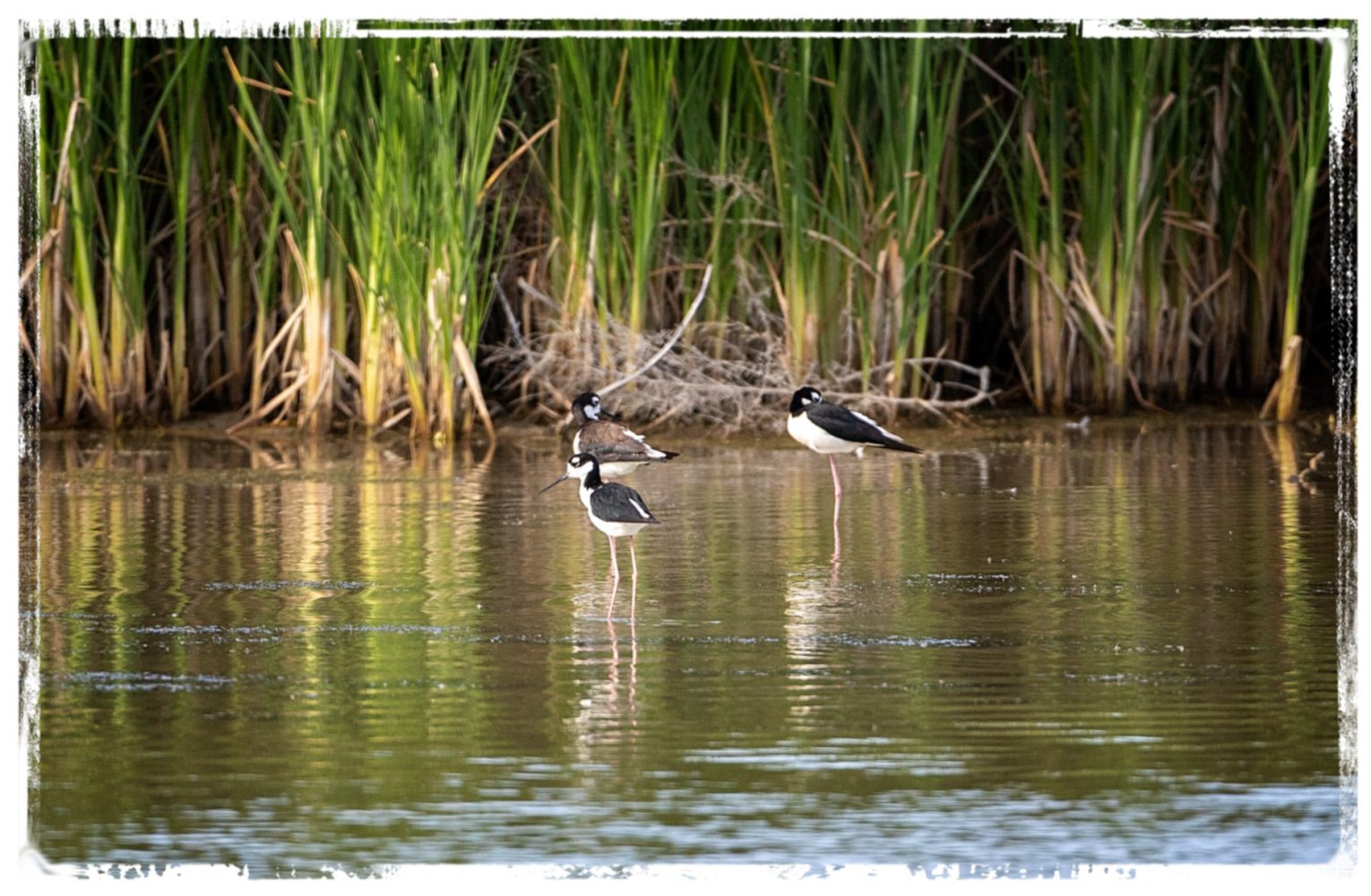

An old saying comes to mind when I look back at our latest trip to Bear River: “Nature abhors a vacuum.” As a gardener, I used to think that saying only applied to my garden where areas I had just weeded would immediately be covered in new weeds. However, it took on a more pleasant connotation when the missing American Avocets, Black-necked Stilts, and Grebes were replaced by large numbers of birds we had rarely seen there, more than ready to take advantage of the wetlands.

One of my favorite of those was the Cinnamon Teal. We were greeted by a pair of very raucous male Cinnamon Teal in the fields before we got to the refuge. I assumed they were squabbling over territory since it was near breeding season.

We were then greeted near the gate by a single male Cinnamon Teal in the pond next to the gate.

I began to question my original premise that males would become territorial this time of year since the opposite seemed to be much more common since most of my shots actually showed pairs or small flocks of male Cinnamon Teal hanging out together.

We only saw a single pair

and they didn’t seem any rush to nest. I was curious about when Cinnamon Teal nest, but the only information I could find online was that they nest “at different times in different areas,” which didn’t really answer my questions.

Thankfully, it’s easy to admire their beauty even when you don’t know much about them, and that’s often the first step in learning about their lives.